The Truth about FADIR, FABER, Hip Injections, and Other Hip Impingement Tests

Failure of Clinical Diagnostic Tests for Identifying FAI is Hiding in Plain Sight. Just Look at the Medical Establishment’s Own Studies.

Table of Contents

- What Are “Special Tests” for Femoroacetabular Impingement?

- Studies Show FADIR’s Lack of Reliability

- Is FABER a Better Test than FADIR?

- FADIR and FABER: What Meta-Analyses Reveal

- Do Hip Injections Hold the Answer to Treating FAI Pain?

- Does Getting Multiple Tests Increase Diagnostic Accuracy?

- How to Beat Hip Pain from a Non-Medical Perspective

The current medical approach for diagnosing femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) relies on tests in order to determine whether someone “needs” surgery, including FADIR and FABER (often dubbed “special tests”), and the use of anesthetic injection into the hip joint.

What do these tests tell us about FAI? Not much, it turns out.

Studies show that FADIR and FABER are scientifically invalid. Relief from hip injections does not predict whether surgery will improve your hip pain and function either.

Let’s look at these tests closely in order to understand why they are misleading.

What Are “Special Tests” for Femoroacetabular Impingement?

In addition to medical imaging such as MRIs and x-rays, traditional medical diagnosis of FAI often relies on tests. There are problems with X-rays and MRI's, but we’re focusing on hip impingement tests in this article.

“Special tests” for FAI are just a series of movements you’re asked to perform with your legs. There is one extremely popular one known as FADIR, which stands for flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. Another is called FABER, an acronym for flexion, abduction, external rotation.

Each simple physical test shows your range of motion and whether certain movements are painful. You might reasonably assume these tests are evidence-based.

But they aren’t.

Studies Show FADIR’s Lack of Reliability

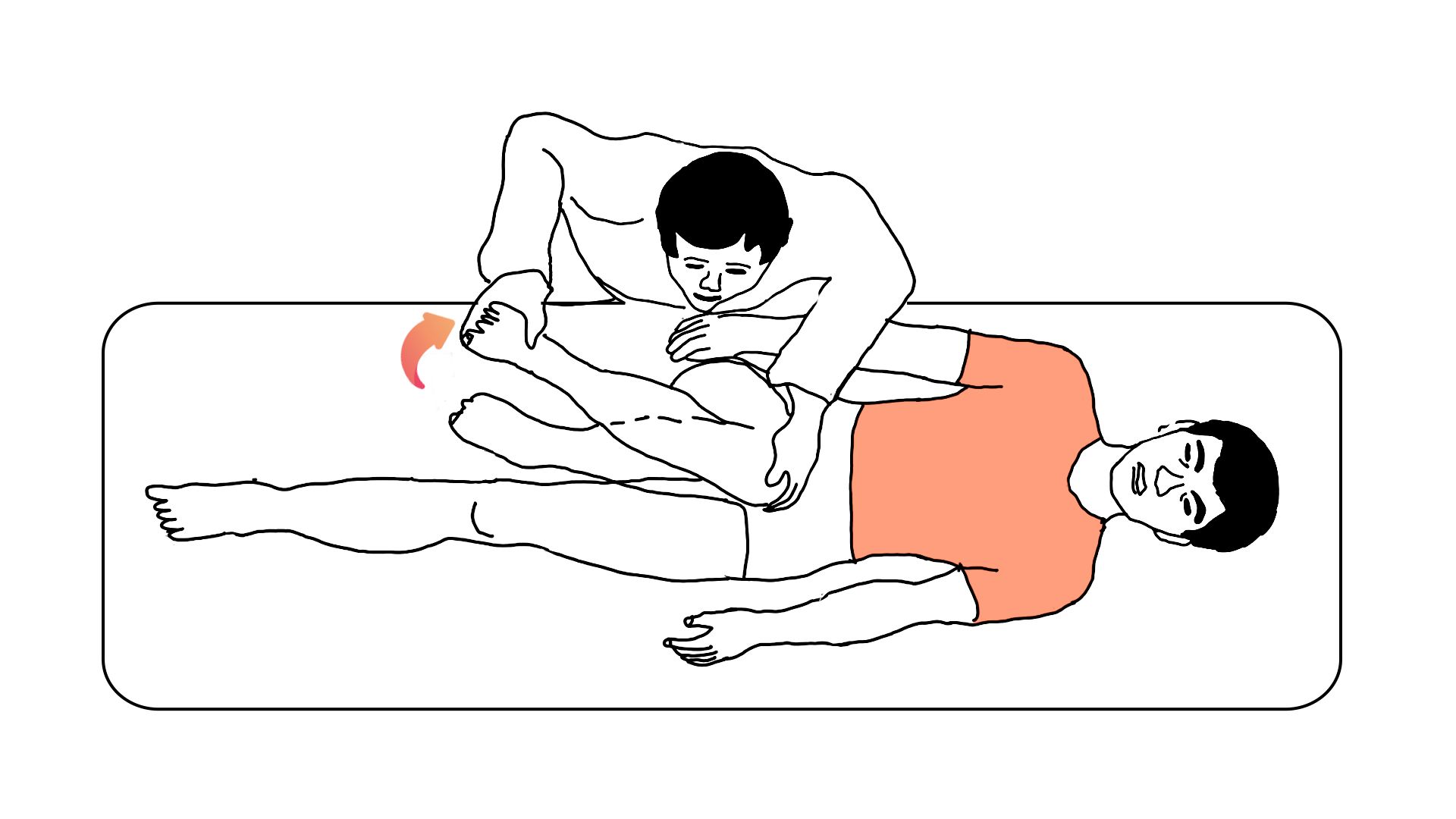

To perform FADIR, a physician moves your knee toward your chest (flexion) then across your midline (adduction). They then move your lower leg, led by your ankle, farther away from your midline while keeping your knee in position (internal rotation).

If you experience pain in the hip during this maneuver, your test result is positive. A positive test is supposed to mean that you have FAI (or at least a very high chance of having FAI). If you don’t have pain, it means you don’t have FAI (or at least have a low chance of having FAI).

No matter what your result is, a doctor will likely still want to confirm the result with an x-ray or MRI. If the orthopedic theory of FAI makes any sense at all, we should see the FADIR test and MRI results match with some degree of concordance. In other words, if the FADIR test is any good, it should yield positive results on people who have FAI bone shapes and negative results on people who don’t have FAI bone shapes.

Yet a 2018 study of FADIR revealed what should have been considered shocking results.

Researchers studied the hips of 74 youth ice hockey players. None were suffering from hip pain nor had previous or ongoing diseases of the hip. Researchers asked them questions about their levels of hip pain and their hip function in daily life, then performed the FADIR test and ordered MRIs for every player. The idea behind this study was that if the FADIR produces pain, the player should have FAI signs on the MRI.

The FADIR test failed miserably.

For the players who had FAI bone shapes in MRIs, the FADIR test only got it right 41 percent of the time. For players who did not have FAI bone shapes, the test was right 47 percent of the time.

In other words, the FADIR test was not even as good as a coin toss for determining whether these players had FAI bone shapes or not!

Interestingly, the researchers did observe that a positive FADIR test correlated with increased hip pain and lower hip function. It just didn’t correlate at all with bone shapes.

The researchers proposed that the FADIR test might be showing the presence of hip pain caused by things like muscle soreness, contractures, or injuries (rather than joint deformity or damage). Given the lack of concordance between the FADIR test and the diagnostic imaging and lack of concordance between imaging and symptoms, this does seem to be the most plausible explanation.

The study wasn’t an outlier. Earlier, in 2013, researchers did a much larger study on FADIR.

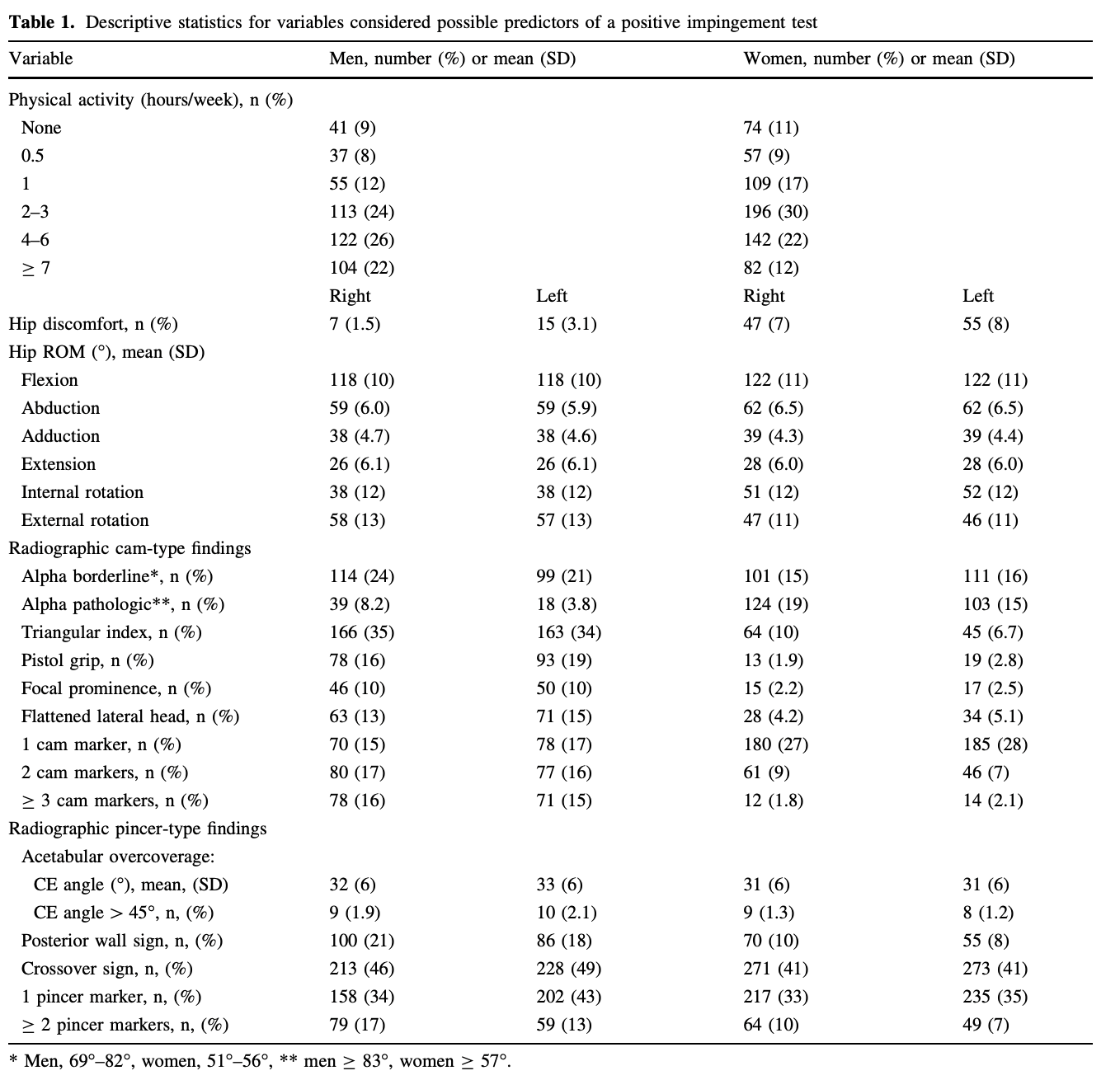

They tested 1,170 healthy 19-year-olds to see how they would do on the FADIR test. Here’s what they found: 7.3 percent of men and 4.8 percent of women had positive test results. The researchers claim in their abstract that the positive FADIR test has some association with the bone shapes. Let’s look a little deeper.

The study kept track of cam and pincer bone shapes in both right and left hips in all the study participants. Looking only at the right hips of men in the study, 48 percent had signs of cam bone shapes, and 51 percent had signs of pincer bone shapes. For women, the numbers are similar: 37.8 percent for cam and 43 percent for pincer. The numbers for the left hips for men and women are similar as well.

That means roughly half of the men and roughly 40 percent of the women had allegedly bad bone shapes. Yet the FADIR test showed positive result percentages only in the single digits, an abysmal correlation with the allegedly bad bone shapes! This study alone should have been ample evidence that the FADIR test doesn’t work. And when we remember that the bone shapes are extremely common in people with no hip disease symptoms, it’s clear that this test does nothing to help figure out whose hip pain might be caused by the bone shapes.

Is FABER a Better Test than FADIR?

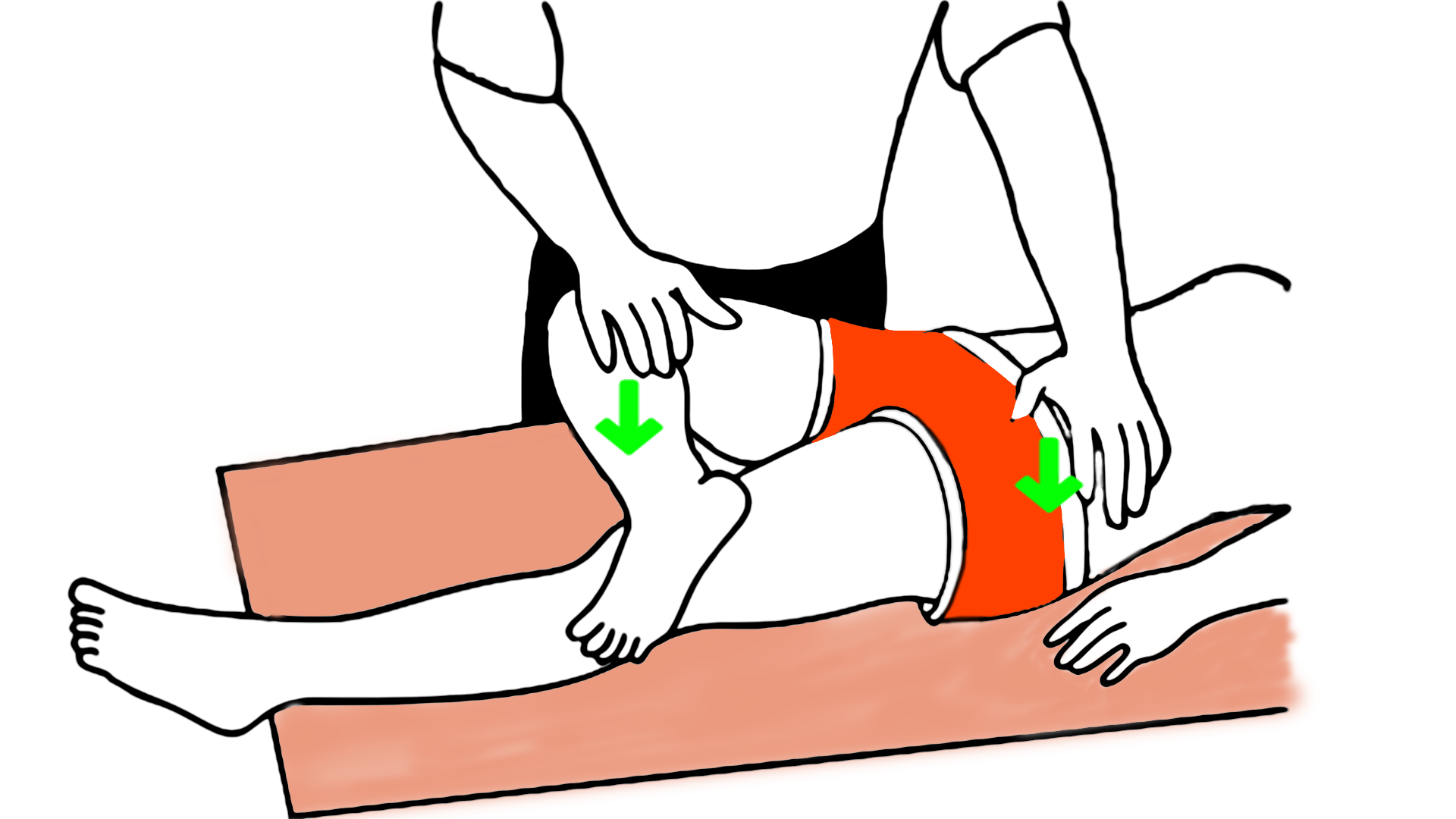

For the FABER test, an examiner brings your knee toward your chest (flexion), then pushes it away from your midline (abduction), and pushes your foot and ankle toward your face (external rotation). If you experience pain near your hip joint, it’s considered a positive result, and you are alleged to have FAI bone shapes.

Now you might be thinking, okay, the FADIR test is apparently not good. But I bet the FABER is good. That's why doctors use both to examine the cause of hip pain for their patients. Nope. And just as with FADIR, there should be some concordance between the result of this physical test and x-rays and MRIs.

Unfortunately that’s not the case.

There’s scant research examining the relationship between the FABER test and x-ray or MRI findings. A 2015 study took on the diagnostic accuracy of FAI clinical tests, FABER particularly, because, the study noted, “Currently, no physical examination tests can accurately confirm or discard the presence of radiographic FAI” and “other studies have been small and suffer from spectrum bias, using subjects with hip pain and intra-articular pathology.” Results were dim, with the study concluding “Clinical tests for FAI generally lack sensitivity.”

And one study published in 2010 compared the FABER test to the results of an anesthetic injection into the hip joint, our next topic of discussion. Researchers examined several physical tests. They hypothesized that if a hip joint injection relieved someone’s hip pain, the physical tests should have been able to identify them as having a hip problem. But they found that FABER had an extremely high rate of false positives. They found results suggesting that when FABER is performed on people whose hips are normal, 75 percent of the time the test would inaccurately say those people had hips with structural deformity.

So, as near as we can tell with limited available research, FABER does just as poorly as FADIR. There is no evidence that a FABER test has any relationship to FAI bone shapes. The only information you can glean from the test is that you have trouble with flexion, abduction, and external rotation. That is a reflection of nothing more than muscle dysfunction and attendant discomfort. It does not necessarily correlate with alleged intra-articular defects, malformed bones, or damage to the joint.

FADIR and FABER: What Meta-Analyses Reveal

Meta-analyses from 2016 and 2020 provide even more assurance that FADIR and FABER should hold little weight in diagnosing FAI.

The 2016 systematic review’s conclusion is direct: “The diagnostic accuracy of physical examination tests to assess FAI is limited … There is a strong need for sound research of high methodological quality in this area.” The researchers basically said that nobody had any good research showing that these tests help diagnosis with accuracy.

The 2020 review uses even stronger language: “Due to the low specificity of clinical tests, we would not recommend their use to confirm the diagnosis of FAI syndrome … we do not have strong information about the interpretability of these test results, that is, there is too high uncertainty due to low-quality evidence and high risk of bias. Therefore, further adequately designed studies in larger populations and with different patient settings are required.”

Keep in mind that when both these meta-studies were published, FADIR and FABER were standard practice. They still are standard practice—and we still don’t have any studies demonstrating that physical tests are valid! There is no evidence that they should be used to convince anyone that they need hip surgery.

Do Hip Injections Hold the Answer to Treating FAI Pain?

Hip injections are another popular diagnostic test the medical industry uses to determine whether you might have a malformed or damaged hip.

Physicians take anesthetic and inject it into your hip joint. Hip surgeons believe that if the injection relieves pain, you have a problem like FAI (or a labral tear) inside your hip joint. Then they’re likely to say you need surgery to fix the problem inside your hip.

Such faith in hip injections might stem from a 2004 paper that claimed that hip injections are 90 percent accurate in detecting deformity or damage in hips. Physicians cite this paper as proof that injections are highly accurate for detecting hip problems.

Look at the study critically, though, and multiple problems surface.

First of all, this was a retrospective study of 40 hip surgery patients. That means that 100 percent of the research subjects had hip pain, and 100 percent ultimately went under the knife. That also means that the surgeon publishing this paper was convinced that every single person in this study had hip joint damage or deformity that would respond to surgery.

The practical implication? Extremely high risk of bias, which means it’s a very low-quality study.

The surgeon reported 37 out of 40 of the patients had a positive response to the hip injections (meaning the injections reduced their pain). Upon surgical inspection, one of those was a false positive (meaning he couldn’t find damage or deformity in the hip joint). The three negative responses (meaning no relief from the injection) were all "false negatives." He determined that they actually did have hip joint damage or deformity.

In other words, the surgeon determined that 39 out of 40 hips had damage that needed surgical correction. The hip injections "missed" three and also got one false positive. Four incorrect answers out of 40 leads to a calculated score of 90 percent accuracy.

But there’s a big problem with this calculation. Many other tests could have performed as well as hip injections because of the extraordinarily tilted sample and the potentially biased determination from the surgeon. A totally bogus test could achieve similar accuracy.

In order to truly gauge the accuracy of the test, you need to ensure that the test accurately identifies positive and negative cases. This study didn’t do that because the sample population was 97.5 percent "damaged."

There was only one patient who was a true negative (no damage or deformity). That means that ANY "test" could have gotten a high accuracy score.

You could use any bogus test setup, but as long as it returned a "positive" result the vast majority of the time, it would look highly accurate.

This Bogus Hip Pain Test Would Be Even More Accurate Than Injections

Think about it this way: You have a bowl of 40 marbles, 39 red and one blue. You take one marble out of the bowl randomly and place it under a napkin so that I cannot see the color.

"Look," I say. "I have a test to determine whether the marble is red. I drop this magic quarter on the table next to the napkin. If it makes a sound, it's a positive result. The marble will be red. If it is silent, it's not red."

We run the test 40 times on all 40 marbles, and my magic quarter makes a sound every single time (as we know, this is because a quarter hitting a table makes a sound every single time).

So what is the accuracy of my magic quarter test? My magic quarter was 97.5 percent accurate!

What if we changed the number of red and blue marbles? Let's say 37 red marbles and three blue marbles. In that case, my test would be 92.5 percent accurate!

If you believe these tests, you've lost your marbles.

But would you trust my magic quarter? Of course not. Why? My magic quarter is good at giving only a "positive" test result. In a test sample where the correct answer is almost always positive, my test does great.

But in a test sample where there are more true negative results, the test would be clearly inaccurate. If we changed the setup with only one red marble and 39 blue marbles, my test would fail spectacularly.

This study claims to have proven that hip injections are highly accurate, but it actually failed to do so because the sample population was guaranteed to make any test look accurate (as long as it turned back a positive result).

What if the sample population were only 50% damaged and 50% perfectly fine? How would the hip injections fare then? Nobody knows with any confidence.

Without more testing on a sample population without hip pain and without hip damage and deformity, nobody can scientifically say hip joint injections are accurate diagnostic tools.

And since it would be questionably ethical to use anesthetic injections and exploratory joint surgery on asymptomatic patients, the true accuracy of hip joint injections is likely to remain unknown.

Hip Injections as a Predictor of Hip Surgery Success

In a 2014 study researchers looked at hip injections another way. They wanted to directly test another strongly-held orthopedic belief. Surgeons will often claim that if a hip injection relieves hip pain for a patient temporarily, it means that fixing underlying hip damage or deformity with surgery will fix the hip pain and dysfunction for the patient.

Researchers gave hip injections to hip pain patients and noted whether they got relief. They performed arthroscopic surgery for FAI for these patients and then followed up over a six-month period. They wanted to see if relief from the hip joint injection did in fact predict better outcomes for the surgery.

Their study results were straightforward. Quoting directly from the abstract: “... a positive response from an intra-articular hip injection is not a strong predictor of short-term functional outcomes following arthroscopic management of FAI.”

In layman’s terms, this means that relief from a hip injection does not predict whether surgery will improve hip pain or function. This study completely undermines the current way hip injections are used to convince people to get hip surgeries.

One potential objection is that the study had a relatively short follow-up period of 6 months. Perhaps the positive benefits of surgery might show up after a year or two?

Given the results of a 2018 hip impingement study with a 2 year follow-up, this seems highly unlikely. In this randomized-controlled trial, one group of hip pain patients got surgery; one group didn't. The conclusion: "there was no significant difference between the groups at 2 years. Most patients perceived little to no change in status at 2 years."

Does Getting Multiple Tests Increase Diagnostic Accuracy?

Short answer: absolutely not. In fact, it's the opposite.

Some surgery proponents claim that if you stack multiple tests, you increase the accuracy of your results. They say that because doctors use MRI and x-rays as well as physical tests, they can fully confirm whether someone’s problems are the result of FAI bone shapes.

This defies logic and basic statistical rules.

The physical tests themselves do not tell you a cause of hip pain. They just demonstrate that someone has hip pain while in a certain physical position, that there is an impediment to comfortable movement. The tests don’t show you anything about bone shapes (since there is no correlation between the shapes and test results, as we’ve already discussed). Nor do they show a cause of the impediment. This goes for every hip pain test on the books.

The 2010 study we talked about earlier examined four hip tests. They found terrible false positive rates for all of them. Most important, researchers found that if they used all the tests on a person, they had a 100 percent chance of telling you that you had a hip problem that would need surgery.

So if you combine FADIR and FABER and then add medical images, you’ve created a situation where you are likely to say anyone with hip pain is a candidate for hip surgery.

But remember, x-rays and MRIs do not show you the cause of hip pain. Remember that multiple studies have shown that the bone shapes themselves are not related to hip pain, the development of hip pain, or the development of alleged structural damage like arthritis. The images only show you the bone shape. They tell you nothing about the cause of hip pain.

If you perform the physical tests and take MRIs and x-rays, you still have nothing that tells you that your hip pain is caused by the bone shapes. You just have a stack of invalid tests that are giving you a false impression.

Let’s look at an analogy.

Let’s say I have a math test and a reading test to give you. I claim that a high score on either the math test or the reading test demonstrates that you have a moderately high IQ. If you score well on both, you have a high IQ.

A research group runs a study and finds that results on these tests do not correlate at all to IQ. Neither one shows any relationship to IQ.

My retort to this research: “Ah, but that’s why I give you two tests! If you score high on both tests, then that provides more evidence that you do have a high IQ! And, look! If we add an MRI of the brain, the size will also show someone with more brain power. So if you take the tests and do an MRI, you will have multiple pieces of evidence to confirm high IQ!”

That would sound ridiculous (because it is ridiculous). Having more invalid tests doesn’t support the conclusion. If you have invalid tests, they are still invalid even if (and especially if) you add more invalid tests!

And for the critical readers out there who are thinking, ah, but the idea of IQ is itself of questionable validity, you’re right. I chose IQ precisely to mirror the situation with FAI; FAI should be viewed as highly questionable as well.

So on this third major point, it seems clear that there is no evidence that the physical tests provide any useful information. They don’t correlate with bone shapes and provide no proven diagnostic value. The injections provide no useful information either.

How to Beat Hip Pain from a Non-Medical Perspective

Tread carefully.

The medical model of hip pain drives people toward injections, reduced activity, and eventual surgery. This tendency is spurred by surgeons' biases and is not backed by evidence.

The real answer is to learn how to retrain your hip muscles for proper motion and function. That is the simplest, least invasive, and natural means to reclaiming your life.

The challenge in this approach is that it requires lifestyle changes and reprioritizing exercise and movement over sitting on chairs and staring at screens. It may also mean giving up certain hobbies and athletic endeavors for a long period as you retrain your body into long-forgotten and disused movement patterns.

How effective is surgery for Femoroacetabular Impingement? Read about Surgery Success Rates for FAI.