Hip injections and joint pathology - 90% reliable for finding the cause of hip pain?

Why am I talking about hip injections?

In a previous post, I shared an orthopedic physician's objections to what we've been talking about with FAI, and in a follow up I talked about hip injections and their reliability and usefulness (spoiler: they don't seem reliable or particularly useful). In case you missed the original YouTube comment from the orthopedic physician, here's a relevant snippet:

Since your [sic] so knowledgeable of the hip joint anatomy I hope you would agree that using a [sic] anesthetic agent and steroid agent to inject into the hip joint would sufficiently rule in or rule out the diagnosis of labral pathology or intra-articular pathology. Guess what? We do it all the time. How could it be that a patient with all the classic findings, along with MRI studies showing labral pathology who receives a diagnostic injection has full relief of pain after this injection simply hours after experiencing severe hip pain? I would love to hear you fumble your way through explaining that one, or use outdated and non-credible sources.

In the response I did on the hip injections, I didn't go into every single study that I've come across. I'm working through a bunch. So, today I want to focus on just ONE study that deals with hip injections and their diagnostic reliability.

This study claims that anesthetic hip injections are 90% reliable for identifying intraarticular causes of hip pain.

Diagnostic Accuracy of Clinical Assessment, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Magnetic Resonance Arthrography, and Intra-articular Injection in Hip Arthroscopy Patients (J. W. Thomas Byrd, MD* and Kay S. Jones, MSN, RN) was a study published in 2004. This study is cited as proof that hip injections can help determine whether someone has pain as a result of something wrong inside the joint.

According to Google, at the time of writing, this study is cited by 241 other articles. It's in the top 50 studies cited in regards to FAI. It's why orthopedic surgeons believe that anesthetic hip injections are so useful for helping you determine where your pain is coming from.

Given that more recent follow up studies show that hip injections really aren't useful in predicting the result you're going to get from surgery, it behooves us to look at the way the study was performed and to see whether its conclusions are as ironclad and reliable as they seem to be.

How was this hip injection study done?

One orthopedic surgeon and his team took a look back at 40 of his patients that he'd performed surgery on. All 40 had hip pain (that's why they were in an orthopedic surgeon's office, after all). This is known as a retrospective study.

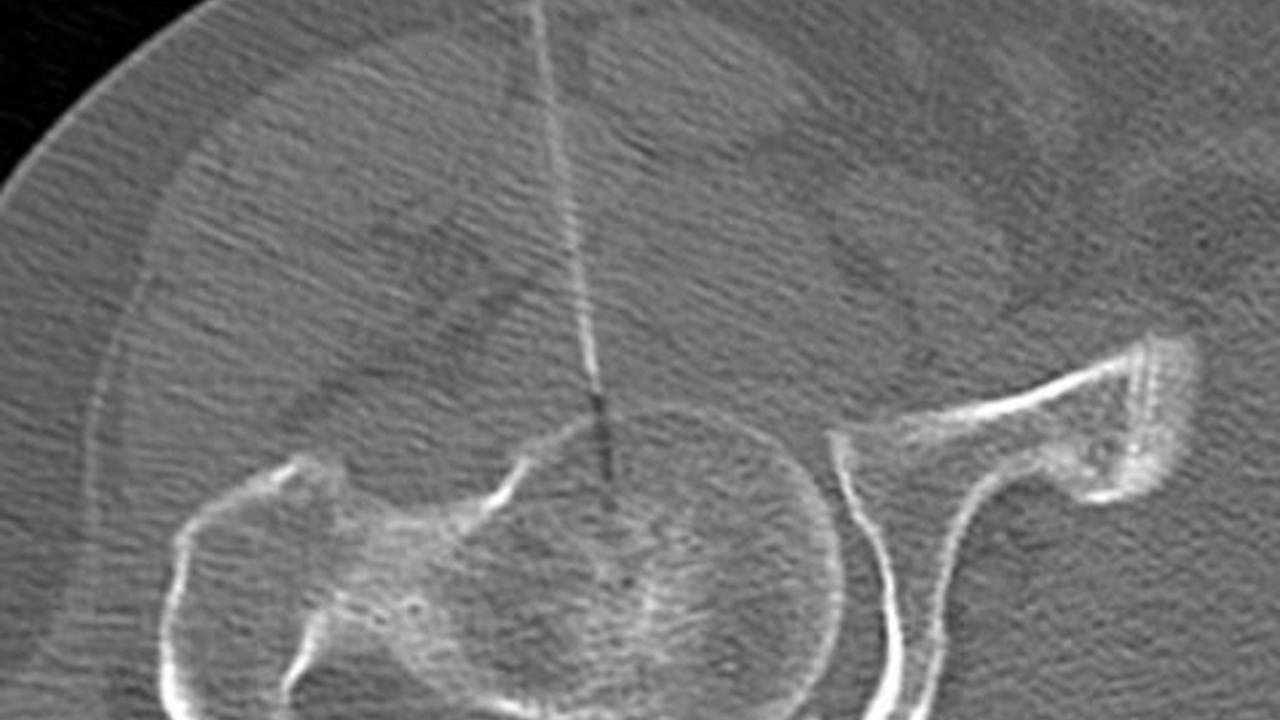

The surgeon had his team do a clinical exam, an MRI, Magnetic Resonance Arthrography, and anesthetic injection. After all that, arthroscopic surgery was performed to see how well the clinical exam, MRI, MRA, and injection matched up to what was found during arthroscopic surgery.

So let's say you're the patient. You go in with hip pain. They do clinical tests, the MRI/MRA/anesthetic injection. They look at the results of each. They want to see how well all these exams compare with the findings in the eventual surgery.

Ideally, they want to see that the clinical assessment, imaging, and anesthetic all point with accuracy to someone having intraarticular problems. This is an attempt to gauge the accuracy of each of these diagnostic methods compared to surgically opening up the joint and looking inside.

This study design is open to lots of inadvertent (and possibly intentional) bias because the one running the study is a surgeon who has a vested interest in performing more surgeries. He also has a bias - during the final surgeries performed - to find pathologies (which could drastically influence the number of pathologies he finds).

What did they find about hip pathology and injections?

Of 40 patients, 97.5%, were eventually found to have some kind of intraarticular problem based on the arthroscopic surgery.

What they reported was that MRI and MRAs were able to detect abnormalities with 67% and 75% specificity respectively, but that they had very high false positive rates (meaning the MRI and MRA indicated problems that were not actually found during surgery). They found that clinical assessments indicated pathology well but not with any specificity (meaning it just meant there was something wrong in the joint, but you really couldn't tell what).

They found that the anesthetic hip injections had a low false positive and low false negative rate and that they were 90% right. We'll dig into how misleading this is after we talk a little more about the MRI and MRA results.

What did they not mention about MRI and hip pathology?

The discussion section briefly mentions the false positive rate of MRIs, but it doesn't really go into it in detail. It also doesn't really discuss the false negative rate. You need to look carefully at the chart and figure it out on your own.

A false positive is when the MRI shows there is something in particular wrong that the surgery shows is not there. This could be a labral tear, chondral damage, or a paralabral cyst for example. If an MRI shows you have a labral tear, but no tear is found during the surgery, it's a false positive.

A false negative is when the MRI says there is nothing wrong, and the surgery shows that there is something wrong in the joint. The MRI and MRA exams proved to be dismally inaccurate - far worse than even the authors reported.

It's important that you know how I calculated the numbers I’m going to share. I looked at each patient's results (provided in a table the study). I counted a false negative only when the MRI said "negative," meaning there was nothing wrong, and the surgery ended up finding something. I did not count instances where the MRI said there was a different problem than the problem that was found during surgery. For example, if the MRI said there was a labral tear but instead there was a chondral defect, I still counted it as a win for the MRI. This means I was being very generous.

For false positives, I did not count every false finding. If the MRI indicated three pathologies and one or all of them were wrong, I counted that as only one case of a false positive - which means I am being more generous to the MRI than I should be. If I counted every single time something was indicated but wasn't found, the number would be higher.

OUT OF 40 PATIENTS:

|

FALSE NEGATIVES |

FALSE POSITIVES |

|

17 |

20 |

If those numbers look dismal to you, you're not alone. In 40 patients, you have 37 cases of either false positives and/or false negatives. The MRI looks more like coin-tossing than anything of acceptable reliability and accuracy at this point.

What did they not mention about MRA and hip pathology?

Now let's look quickly at the MRAs and see how those fared. As noted previously in the discussion, the MRAs are supposedly more accurate. I used the same counting methodology here as I did for MRIs.

OUT OF 40 PATIENTS:

|

FALSE NEGATIVES |

FALSE POSITIVES |

|

3 (100% of the negatives given) |

19 |

Should that inspire confidence in the MRIs or MRAs? What you are seeing is an approximately 50% false positive incidence for both MRI and MRA.

The low false negative rate on the MRA is due to the fact that the MRA seemed to indicate pathology at much higher rates than MRIs in general, and 97.5% of the patients had "pathology" in the joint. The three times it actually gave a negative (no pathology) indication, it was wrong.

The weakness of this hip injection study isn't obvious - but it's important.

There are two huge issues with this study that undermine the conclusion.

- There is no follow up about actual pain relief for the patients. This is hugely important. The actual success of the surgery in relieving pain needs to be examined to determine if the pathologies were the cause of pain. This cannot be overlooked, especially since a recent study in 2012 showed that 73% of a totally asymptomatic group had evidence of abnormalities and that 69% had labral tears.

- There were no opportunities for false positives.

- 97% of the patients had intraarticular pathology. The only way the injections could have NOT worked would be if they had given false negatives. But this is an anesthetic that blocks the sensation of pain.

- The final results of the study showed only one patient who had a normal hip joint upon arthroscopic inspection. In fact, that patient's MRI, MRA, and injection all pointed to intraarticular pathology. In the end, despite all evidence, the patient had no intraarticular pathology.

1. Pathology and pain have to be shown to be related: an analogy

The biggest problem here is that the connection between the pathologies in the hip and the actual symptoms is never clearly demonstrated. More recent studies show there's no correlation between these pathologies and symptoms. As for the accuracy of diagnosis, the effect of the anesthetic is not known to actually be specific to ONLY intraarticular pain. That was simply assumed.

But because it is an anesthetic, it's totally probable (and in my opinion highly likely) that the anesthetic does affect pain in the hip regardless of where the pain originates. Anesthetic numbs things. It's purpose is to block pain.

2. The sample is extremely biased, so any test could've shown 90% accuracy

The population used for this study was highly biased towards the positive end. Because 97.5% of the patients were found to have intraarticular problems, essentially ANY "test" that returned positive signals would have turned out with the same high "accuracy" rate as the injection.

The authors of this study believed that if an anesthetic injection into the hip joint reduced a patient’s hip pain, it was a sign that pathology in the hip joint itself is the cause. Examples of pathology would be a labral tear, a paralabral cyst, or some kind of bone degeneration, etc.

37 out of 40 of the patients had a positive response to the injections (meaning the injections reduced their pain). Upon surgical inspection, it turned out that one of those was a false positive. The three negative responses (meaning no relief and therefore no hip joint problems) indicated were all false negatives (something was found during surgery). 4 incorrect answers out of 40 leads to a calculated score of 90% accuracy.

But that’s not really an accurate interpretation.

Upon surgical inspection, 39 out of 40 patients (97.5%) of the patients turned out to have intraarticular abnormalities. That means that any test that has a tendency to return “positive” findings for pathology would have turned out with a similarly high accuracy rate as the injection.

Suppose they had used a fictional and silly belly button skin pinch test to look for pathology. The skin pinch test would be simple and cheap: if pinching the skin just below the belly button hurts, it's a sign of intraarticular hip joint pathology.

Running this test on the same group of 40 people, let’s assume that it hurts on all 40 people. This positive finding would yield a higher accuracy rate than the injection! 97.5%! And only one false positive!

Suppose they had used a "flinch test." If a patient flinches when you throw a fake punch at them, they have intraarticular pathology. All 40 patients flinch. 97.5%! And only one false positive!

The injections only achieved 90% because the deck is stacked in favor of any test that returns positive findings.

What makes this study seem convincing is that the test took place at the hip joint, but it's very unclear what effect anesthetic has on a hip joint that has pain and no hip joint pathology. And it is also NOT unlikely that an anesthetic injection into the hip joint may also block the sensation of pain, even if it is actually caused by something outside the joint. Of course, investigating this would be extremely difficult since the prevalence of hip pathology in relatively young asymptomatic individuals can be as high as 73%. This means 73% of people with NO symptoms already have hip "pathology." So you would need to find people with hip pain and no pathology and use the anesthetic injection to see if the anesthetic has an effect on their pain (and I would wager it would, since it is a numbing agent).

Final thoughts

What's most troubling about this study is that it's cited so often as evidence that diagnostic hip injections are reliable indicators of hip pathology. More recent studies have demonstrated that hip injections are not at all predictive of surgical success, but this study continues to be used as justification for hip injections.

Another troubling issue is the extremely high false positive and false negative rates on MRI and MRA. This gets glossed over in the study, but it's well worth noting since both tools are used to provide the sense of certainty where none exists - especially given the high number of people who have totally asymptomatic hip "pathology."

Unfortunately, it's becoming clear that the science upon which surgery for FAI is more problematic than I even suspected when I first started researching this. If you're someone critically considering the theory of surgery for FAI, it is very much worth your time to dig deeper and deeper.